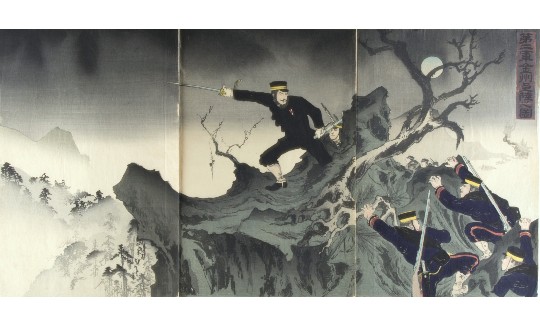

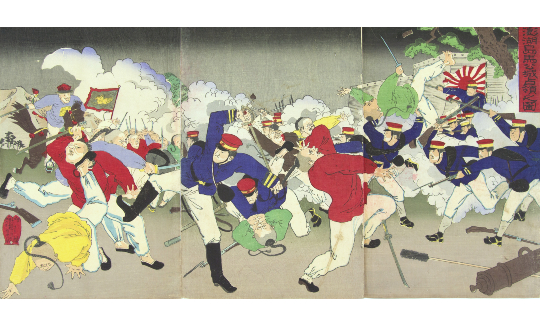

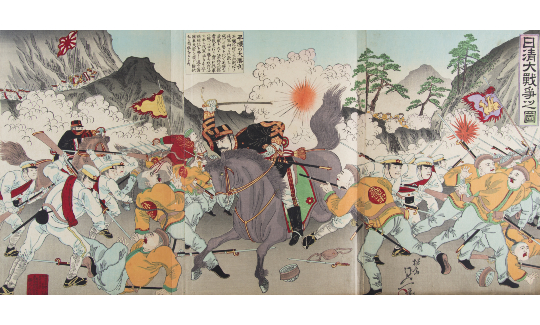

Winds of War Japanese Propaganda Prints of the First Sino-Japanese War and the Russo-Japanese War

More info:

046030800In the mid-19th century, following a period of two hundred and fifty years of seclusion, Japan opened its gates to the West and trade relations with various countries were established. In addition, Japan formed a large army in order to protect its strategic interests in neighboring countries, as did many other world powers of the time.

At the end of the 19th century, Japan's territorial disputes with China on Korean soil increased and it sent troops to the region. In the early 20th century, Japan did so once again, in a similar conflict with Russia. During the Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895) and the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905), the Japanese army fought on various fronts in Korea and in Manchuria, China.

During the first modern wars of Japan, many artists began to design propaganda prints, praising their army and describing the fierce battles in which it fought. Sensô-e (war pictures) was the last genre in the tradition of Japanese woodblock prints known as ukiyo-e (images of the floating world), dating back to the 17th century. Before war prints appeared, woodblock prints mainly depicted Kabuki actors, pleasure quarters (yûkaku) and pleasure girls (yûjo) who served their clients, sumô wrestling, landscape etc. Many prints were used as posters for advertisement.

Woodblock prints played an informative role even before the appearance of the sensô-e genre. They evoked a sense of "Japaneseness", contributing to their efficiency as a means of propaganda. War prints were considered historical documents and were very popular in their time. However, art historians did not consider them to be works of art as they were narrative in nature, and therefore they rarely appeared in Western art books.

Except for the Japanese intellectuals, who appreciated the Chinese and the Russian cultures through their wonderful literature, common people depended on the popular media to characterize the enemy. Before the Meiji period, Japanese artists had little experience in illustrating foreign armies. This is due to the fact that Japanese artworks, which preceded the modern-era wars of Japan, dealt mainly with internal wars. Likewise, Japanese artists knew very little about war in general, and therefore their designs took an emotional approach.

The Japanese had always appreciated stories about the courage and the loyalty of the samurai. Prints by numerous artists, which depicted the heroes of the past, were used as prototypes for war prints designers. However, the Meiji era was characterized by great eclecticism - artists chose their sources of inspiration from various styles of painting available to them. For instance, lyrical landscapes in some war prints are based on tonal effects of ink and colour that appear in the landscape paintings of the Shijô School. Increased contact with the West and the development of yôga (Western-style painting) provided yet another source of realism in their art. Japanese style (nihonga) and Western-style painting were combined in historical paintings of the Meiji era. In addition, artists were inspired by lithographs and photographs appearing in newspapers and periodicals. These media depicted warfare that took place in the west.

War prints of the Meiji era are the first instance in which illustrations of the enemy were used to influence public opinion to support Japan's foreign policy. They achieved this by encouraging emotions of loyalty and patriotism. For example, Kobayashi Toshimitsu (active mid to late 19th century), who was a student of Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892) illustrated the Chinese soldiers as beasts, during the fall of Pyongyang in the Sino-Japanese War. Donald Keene and other scholars regarded this as an expression of the rise of racism in Japan during the war. However, in Russo-Japanese War prints, Russian soldiers are no longer presented in this manner.

During Japan's early modern wars, artists abandoned almost all other genres, concentrating mainly in designing war prints, since they were in great demand. While the artistic design and technique remained traditional, the subjects was new - the Sino-Japanese and the Russo-Japanese Wars. These prints continued the tradition of warrior prints and historical battles. Nevertheless, foreign armies were depicted in Japanese art for the first time.

Western periodicals, available in Tokyo during both wars, provided the subject matter for print designers. Photography was also an important source of inspiration and some artists based their designs on photographs. Precise and meticulous descriptions of weapons and battleships, mainly in the Russo-Japanese War prints, were made by carefully studying photographs.

Most common compositions of war prints originated from the artworks of the Utagawa School. Architectural elements and landscapes served as a backdrop for the scenes and were meant to hint at the locations where they were taking place. Another template that was in use in war prints originated in Western art – creating spatial depth by placing the landscape on the rear plane.

Prints were part of the Japanese advertising industry up until the course of the early modern wars. They were part of the "yellow journalism" that covered the war. Some believe that war prints promoted government policy by stirring up emotions of unity in the hearts of the Japanese people in times of war. They were also intended to change and shape public opinion in order to convince the Japanese that their country was fighting a just war. Did war prints in fact play such an important role in this era? Maybe so. However, one must not forget that they were also a commercial product. The government did not employ publishers, artists, carvers and printers and they did not act on its behalf or at its service. The publishers were private businesses purchasing designs for woodblock prints directly from the artists.

The artists were professional painters who lived from their artisanship. The payment for a triptych print design was relatively low at the time. Yoshitoshi, who is considered the originator of the war prints genre, earned between 3.5-5 yen for designing a print of the Satsuma Rebellion (1877), and a decade later, he was paid about 10 yen per print. From the 19th century onwards, woodblock carvers belonged to an independent guild and were no longer considered the publisher’s employees. Thus, it was necessary to pay for their services as well.

Publishers strived to distribute colourful prints that would be appealing for customers and would be sold in as many copies as possible. Their purpose was to increase their profits. However, the Japanese authorities enforced a strict censorship over the production of woodblock prints. Sever censorship was particularly enforced during the Russo-Japanese War, which was costly and bloody and therefore, the government saw the need to control the publications and their outcomes. Even though, the publishers recognized the opportunity to sell woodblock prints of a new genre and encouraged the production of war-related images. Traditionally, about 250 copies of a colour print were printed per day. These copies are considered to be the first edition of the print. In contrast, when war prints appeared, tens of thousands of copies of each image were printed. This resulted in a gradual reduction in the quality of the woodblocks plates. Further, in order to reduce printing costs, some publishers chose to reduce the number of colour plates used. Prints were published in two editions: a simple edition intended for women and children, and an elegant one. War prints were also presented to Emperor Meiji. There is no doubt that colourful prints sold in albums were more attractive than the monochrome photographs published by the press.

In addition to painting in Japanese style or Western-style, most print designers were also illustrators of newspapers and books. Numerous cartoons, drawings and colourful woodblock prints were printed in newspapers alongside photographs of the battles.

In addition to their given names, Japanese artists also adopted artistic names. Some are known only by their artistic names, which appear as signatures and seals on their prints. Artists may have adopted a new artistic name especially for this genre. Various artists, including Mizuno Toshikata (1866-1908) and Migita Toshihide (1862-1925), used to add the inscription "by order" (ôju) before their signatures. These additions not only indicated that the publishers ordered the prints, but alleged that the artworks were of great demand.

In general, war prints included scenes of battles fought by the Japanese army with modern battleships and weapons, or portraits of high-ranking officers and courageous soldiers. Patriotic citizens were eager to purchase these prints, and the competition between the publishers over customers was intense.

New prints were designed, printed and distributed just as soon as reports from the battlefield were published. Prints depicting scenes of pre-anticipated events were designed in advance to speed up the process. Occasionally, images of events that did not occur at all were printed. These prints were of poorer quality. However, talented artists like Yôshû Chikanobu (1818-1912), Watanabe Nobukazu (1872-1944), Mizuno Toshikata and Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847-1915) managed to design extraordinary artworks. Historian Donald Keene estimated that ten new prints were designed daily during the Sino-Japanese War and that a total of 3,000 different triptychs were published along this war. During the Russo-Japanese War, fewer prints were published as photography became more available. Kiyochika designed more than 80 different triptychs during the Sino-Japanese War. Toshikata, Toshihide and other artists were also very productive.

Most of the print artists resided in Tokyo during the wars. They received information about the battlefield through press releases, photographs and illustrations. Many Russo-Japanese War prints are very similar to those of the Sino-Japanese War. Thus, they are unlikely to be based on actual observations of the artists on the battlefield. However, in order to convince the customers that the scenes were authentic, the artists employed a realistic style in their prints. For example, Kobayashi Kiyochika's dramatic and exaggerated contrast of light and shadow in his prints was derived from the study of photographs. Prints preserved in special albums, were made with embossments (karazuri) and special effects in order to increase the sense of "realism" in art. The colours of these prints are well preserved because they were not exposed to light for long periods.

Many war prints contain detailed titles and inscriptions that describe events taking place on the frontlines. These captions contributed to the sensation that the prints accurately described current events. The desire to present ”real reports” also appeared in light of the fierce competition between the publishers and the press that included photographs of the battle zones. This reinforces the fact that the publishers’ main goal was to increase print sales as much as possible. Woodblock prints were colourful and carefully designed. Therefore, they attracted more attention than the black-and-white photographs, which were not ascribed artistic value. In addition, the prints’ artistic style retained the poetic quality of landscape drawings.

Propaganda art worldwide used to describe enemies with racist and humiliating stereotypes. For example, a picture published in St. Petersburg during the Russo-Japanese War illustrated a tall Russian soldier beating a small, crooked legged, Japanese soldier. Likewise, Japanese propaganda prints illustrated the Chinese soldiers as inferior to the modern and moral Japanese soldiers. Japanese artists repeatedly illustrated the defeat of the enemy, although occasionally a Chinese or a Russian commander whose heroism equaled that of the Japanese ideal, was also portrayed in war prints. Nevertheless, the central theme of these prints was always a hymn of praise for the Japanese Empire.

War prints portrayed the victories in the battles and the comradeship of the Japanese soldiers. In general, the war was presented in an idealistic manner - hardly a single drop of blood was shed. Japanese censorship hid the horrors of the war – the soldiers who suffered frostbite during the Sino-Japanese War and thousands of soldiers killed in the attempts to capture Port Arthur in the Russo-Japanese War. The censorship’s aim was that the Japanese people would continue to believe that the war was rightful and necessary.

The government’s desire to gain the people’s support over the war efforts and the publishers' desire to become rich did not contradict each other. Domestic customers of war prints yearned for the constant depictions of the victorious Japanese army. These specific illustrations benefited both the sale of prints and the government’s needs. Okamoto Shumpei, in his book "The Japanese Oligarchy and the Russo-Japanese War" (1970), claims that articles about the war in the Japanese press were usually written by the "soft reporters", who remained in Japan during the war. These reporters added sensational and inaccurate descriptions of the battles. They also wrote about the heroic actions of individual soldiers. Woodblock prints, as well, depicted heroic individuals. For instance, private Harada Jûkichi, sergeant Kawasaki Iseo and officers Ôshima, Fukushima and Nuzu, who showed their courage and endeavor according to the samurai code, an essential value for every citizen in the Meiji period. Prints of the Sino-Japanese War illustrate the heroic soldier, while those of the Russo-Japanese War do so less. Depictions of heroes from all strata of society and military ranks were part of the effort to bring the news of the war to the common people. These were heroes with whom the crowds could identify and thus it made recruiting young men to the army far easier.

The English titles, which appear on some of the Sino-Japanese War prints and on a larger number of the Russo-Japanese War prints, indicate that there was also an English-speaking audience that admired those prints.

The prints of the Sino-Japanese War and the Russo-Japanese War continued the tradition of the warrior prints, but they were also part of the biased press that assisted the government's policy of creating a sense of nationalism and unity among the people. The heroic images of the Japanese soldiers stirred deep emotional reactions and ignited the fire of patriotism. Although the prints were of a commercial nature, they also were designed to convince the Japanese public that Japan is a celebrated nation that fights a just war.

We would like to thank Mr. Yoel Shagan for his generous donation of Japanese war prints in memory of his wife Tzvia Shagan and of his daughter Oranit (Shagan) Talmor. These prints, which symbolize the conclusion of the ukiyo-e genre, are the first of their kind to be exhibited at the Tikotin Museum of Japanese Art. The collection donated to the museum comes in addition to the collection of porcelain donated in the previous year by Maya and Guy Talmor, in memory of their mother, Oranit (Shagan) Talmor.

We are also grateful to Mr. Ofer Shagan, to whom the collection first belonged, for enriching the museum's collections. We thank Mr. Shagan for his close friendship and active cooperation with the Museum, which have led to the successful and well attended exhibitions, "The Art of Love" (2009), "Love with Humour" (2017) and “Blue and White” (2018), loaned from his private collection.