In every society and culture worldwide, the wind plays a vital role - as a metaphysical phenomenon, as a source of power, in art and literature. Attitudes to the wind are usually ambivalent. On one hand we can obtain energy from it; and on the other it has force enough to kill and destroy. Inhabitants of coasts or islands, like the Japanese, are particularly affected by the wind. One could say that in ancient times, peoples' lives were regulated by it. The Japanese use the term kaze (wind) in many different contexts, and with different connotations. We find it, for example, in the lively figures of the manga (Japanese comics), or in kamikaze (Divine Wind).

The wind has certainly intrigued many artists throughout history. Piero Manzoni (1933-1963), for example, sold "Artists' Breaths", and Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) flew to New York in 1919 with "Air from Paris" in a little glass flask. In the same year he also created "Unhappy Readymade" - a geometry book that was hung out-of-doors so that the wind could turn the pages and "select" the problems "it" wanted to solve.

The contemporary Japanese artist Rikuo Ueda loves the wind. His works deal with the phenomenon of wind and its motion. He creates paintings with the wind's help, turning Nature into a creative artist by attaching writing or painting implements to trees and other plants. The wind blows through the branches, and they leave their traces on the paper or canvas. Thus he exposes the invisible creations of Nature. While Duchamp was interested in the random creations of the wind, Ueda is essentially interested in documenting its movements.

At the age of 23, Ueda left Japan on a trip that lasted for three years. His encounter with people from other lands and cultures helped him to reaffirm the Japanese Buddhist tradition in which he had been raised, and he decided to become an artist. In 1997, while living on the stormy coast of Denmark, Ueda constantly felt that he would like to "catch the wind". He tried to trap it in various receptacles, and started a "collection" of winds. Wherever he went, he took with him a tin to hold the wind he had caught. For him, the wind is an element that connects everything, without beginning, middle, or end, embodying the Buddhist concept of transience (subete wa utsuru) similar to panta rei (everything flows), the philosophy of Heraclitus.

In Denmark, Ueda met the artist Steen Rasmussen, who had also done much travelling and was interested in the wind as a natural phenomenon that everyone experiences. "The wind has two faces" he says. "It kills and revives. A hurricane can wreck a building, kill people and animals, and destroy plants. Conversely, it helps the plants to disseminate their seeds everywhere, and those seeds sprout and supply food to people and animals."

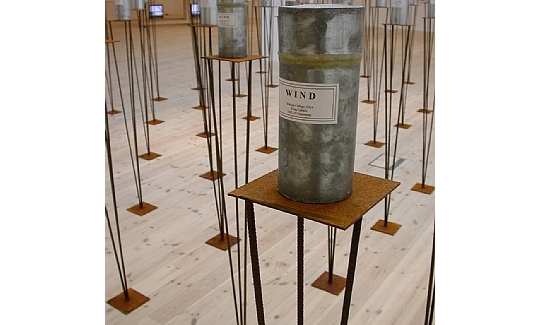

Since 2001, Rikuo Ueda and Steen Rasmussen have been cooperating in a grand initiative. They have collected wind in signed tins from sites throughout the world, including Israel, the Palestinian territories, Japan, Denmark, Germany, Holland, Belgium, Sweden, Luxembourg, Italy, Poland, America, and elsewhere. They have asked people in various countries to collect the wind in tins and to document the event in photographs to integrate in their installation. The photographs tell us about the people who caught the wind, and about how they reacted when asked to do the impossible - to catch wind in a tin can. Some of them look embarrassed, while others are relaxed, open to the experience.

The installation can also be interpreted as a map of Ueda's and Rasmussen's travels, because one of them is always present when the wind is being collected. The artists have already amassed 150 tins. On each tin displayed on a wooden post there is an attestation of where the wind was collected. The regular spacing of the tins and their accompanying pictures creates a sense of serenity and harmony. And though, at first glance, all the elements of the installation look the same, closer scrutiny reveals their differences.

This vast, ongoing enterprise is, in fact, a dialogue that ignores geographic and political boundaries worldwide. Ueda and Rasmussen are fascinated by the experience of perceiving the invisible: "You can't see the wind, only its effect on the material world. Thus we are catching the immaterial by means of the material" they conclude.