The question of the "original edition" or the "later edition" of the traditional Japanese woodblock prints has aroused much interest in students of Japanese art, and is a source of concern to collectors. Another matter related to this question is whether the carved wooden blocks used for this or that print are the originals, or whether part or all of them have been replaced by new ones. Blocks for popular prints such as those by Ando Hiroshige or Kitagawa Utamaro were re-created, and many new prints were made from them. As a rule, such prints are presented as reproductions, but sometimes, perhaps due to lack of knowledge, or even the intention to deceive, they are displayed or sold as originals. Accordingly the collector of woodblock prints must either acquire information that can assist in deciding whether a print is original or not, or trust to the integrity of the vendor. The originality of a print is confirmed when the collector knows both how to read the seals that appear in the margins, and the period in which it was created.

A traditional Japanese woodblock print is considered "original" if it was printed during the artist's lifetime. The artist prepared the sketch from which the key block was carved with the (usually black) outlines, as well as the original wooden blocks for printing the various colours. The reprint is a later copy printed from these original blocks. For such prints, cheaper paper was usually used, as well as fewer colour blocks, and special effects such as colour transference, blind printing and mica (sparkle) were omitted. A print that also include slight modifications in the key block (not always with the artist's permission) or in any of the original blocks is considered as a reprint of the work. These are defined as "different states".

The "state" is a print made from a specific set of carved blocks. Exchanging any of the original blocks for a different one creates a different "state" from that of the original design. A new "state" depends on the publisher's decision to remove one or more blocks from the set, or sometimes the carver might decide to change an existing block for another, or even add more blocks. All such "states" are considered as originals if they were made during the artist's lifetime. On the other hand, an "edition" is a print with specific characteristics of the "state". Differences between editions derive from different methods of printing the same blocks rather than from replacing, adding, or removing blocks. A new edition is printed when the printer decides to change the colours, or to add or discard various techniques such as overprinting, use of metallic colours, blind printing or shading.

Prior to the Meiji era (Meiji: 1868-1912) there were no artists' rights in Japan. The carved blocks were the property (zohan) of the publisher (hanmoto) or of his shop (honya), and not of the artist. Blocks sometimes changed hands or were sold to another publisher (kyuhan, guhan: purchased/acquired blocks). Reprints were frequently issued by the publisher who had acquired the blocks. The value of such prints depended on their closeness to the originals and the proximity of their time of printing to that of the earlier editions.

Experts use the terms "early", "middle", or "late" only in regard to editions for evaluating the quality of original prints. Those printed after the artist's death are worth less. There are almost no edition printed from a completely new set of blocks that had been prepared during the artist's lifetime, and all editions are very similar to the artist's original design, some of them even prepared according to his artistic methodology.

Reproductions are made from new woodblocks carved according to the artist's original design. Conversely, prints from new blocks created with the artist's or the publisher's permission, because the original blocks were inferior or lost, were not considered as reproductions. Many reproductions were printed during the Meiji era, and many new reproductions of traditional prints are still being produced today. A forgery, on the other hand, is a reproduction intended to convince that it is an original. Forgeries are often printed on old paper, or on paper that looks old. Technically, there is no difference between a forged print and a reproduction. In most cases there were no pirated editions of an artist's work made during his lifetime without his permission or that of the publisher who owned the original blocks. These prints are not considered as originals, either by artists or by collectors, but are accepted as genuine because they were created during the Edo period (1603-1868), i.e. when the originals were printed.

Many copies were made of each print. The number of colour prints completed by a printer during a working week, is estimated at about 200 copies. Kawasaki Kyosen, son of the artist Ichiyusai Yoshitaki

(1841-1899) confirms this number in his essay on "How to Prepare Colour Prints" (Nishiki-e ni naru made). More copies were printed later, according to orders, each time in batches of 200. Thus the requested copies could be numbered in hundreds or even thousands. A biography of the artist Utagawa Kunisada (1786-1864), written at the close of the 19th century, states that 3 - 4 thousand copies were printed from the original blocks of some of his prints. However, we must take into account that many prints have been lost in natural disasters such as earthquakes or fires in Japan. Surimono prints (surimono: something printed) are more expensive and rarer. They were intended for private publication for special events, and were published in limited editions of 200, or sometimes 500 prints.

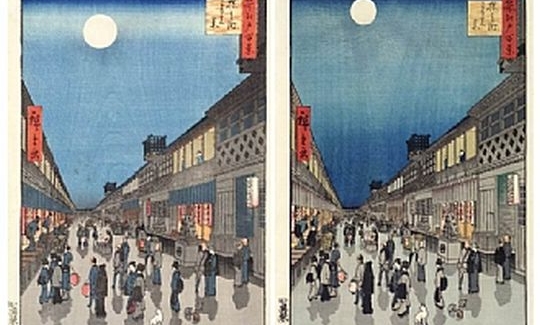

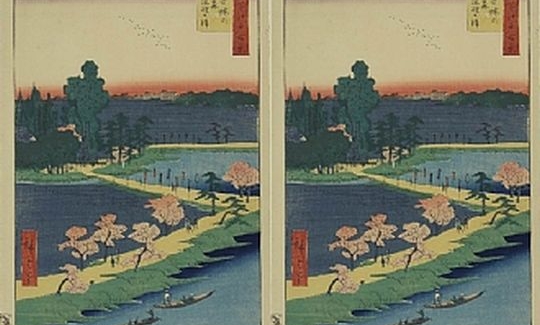

Prints or series of prints in great demand were created 5,000 or 10,000 times over several years. Printing so many copies wears down the block so that outlines are no longer sharp, and are even broken in some cases. As regards colour, there is also a difference between earlier and late prints. The first examples were very accurate, according to the artist's intention. Later, usually after the blocks had been acquired by another publisher, reduction in quality of the colour is very apparent.

Whether a copy from an edition is early or late is decided after careful examination of its quality. For example, in the early copies, the outlines of the key blocks are clear and sharp. Those in the middle range are less clear, and in the late issues, they are blurred or broken in places.

It is not always easy to decide how many colour blocks were used for the early copies, especially if colours have been overprinted. Furthermore, it can be assumed that we will never know exactly how many editions were published or the exact number of prints in any specific edition. The series "Fifty-three famous views of the Tokaido Stations" by Ando Hiroshige, for example, first published in 1855, was printed again and again from the original blocks right up to the 1880s. Relying on the wear of the blocks in order to estimate the number of prints is difficult because damage or wear might have occurred during earlier printings.

Experts and collectors agree that the earlier the print the better the quality because the images are sharper and the colours more accurately applied. Later prints are usually from less expensive editions, printed by publishers who acquired the blocks. Such editions were created with fewer colour blocks and less refined techniques, in order to economize on costs and on time.

Evaluating the quality of a print demands great expertise. Generally speaking, clearer and sharper lines and more accurate placing of colour are considered better. To ascertain whether a print is an original necessitates comparison with a print whose provenance is established. Since it is very difficult to obtain such works merely for this purpose, it is possible to make comparisons with high-quality enlargements in books.

Close scrutiny of a print involves examining outlines, quality of colour, type and size of paper, the carving style of the woodblocks, quality of printing, and likelihood of re-printing. Most important of all is comparing the outlines of the key block carved according to the artist's drawing. Every line must be examined, including calligraphy, to see whether thickness, direction and angle are identical with the original. Intensive study has revealed that, in almost all copies, there are slight variations in line from the original print. It must be borne in mind that the original prints were handmade, and that even in these there are slight differences deriving from wear and tear of the blocks, size of paper, colour that has been mixed or absorbed differently by the paper, or because the printer's pressure has varied in some areas. Such flaws are more obvious in printings from the colour blocks.

The types of paper used for prints vary in quality, but one cannot rely solely on the paper because during the Meiji era they used the same type of paper for printing reproductions. In the early prints one can see the picture on the reverse of the paper. This is not the case in many modern prints. Sizes of paper have also changed, and larger sheets seem to be preferred for later prints. The thickness of handmade paper also varies. Modern paper is frequently more rigid and smoother. Storage can also affect the paper. For example, a print glued to a surface or to paper that is not acid-free has a different texture from those that have been carefully stored in appropriate conditions.

A further element in the identification process is the quality of the woodblock carving and of the printing itself. In prints from the Edo era, the outlines are usually more ‘calligraphic' than those of modern reproductions. In the originals the lines look almost like brushstrokes, also due to the much greater absorbency of the paper; while in 20th century reproductions there is an evident tendency to sharply defined and unified lines. Of course there are exceptions, so this too must be evaluated with caution.

The provenance of a print can also be established by studying the colours. In the 18th- and 19th -century prints, some colours had a unique transparency and texture that only the practised eye can discern. As a rule, the transparency of a colour and how it is absorbed by the paper are what make the difference. Printers and publishers sometimes attempted to create prints with different colours, and the choice of colour must also be examined carefully because the colours themselves may change due to continued exposure to light. Conversely, the pattern of the woodblock fibres in larger areas resembles fingerprints - a simple test that anyone can make.

The size of a print also offers a clue, though modern prints usually adhere to the original sizes. Thus we must take into account all of these elements, and also that publishers would not invest effort or money in producing prints that were not sufficiently popular to be profitable.