In 1998 the Tikotin Museum of Japanese Art presented the first exhibition in Israel of the works of the calligraphic artist Kazuo Ishii. During his studies, Ishii learned to write all the kanji - the Chinese calligraphic symbols that had developed over time- kimbun (bronze-vessel style script), daiten (great seal script), shoten (small seal script), mokkan (wooden-tablet script), reisho (clerk's script), kaisho (official script), gyosho (semi-cursive script), and sosho (cursive script), bokuseki (literally: ink trace) - used by the Zen monks, and the Japanese hiragana - phonetic symbols. Ishii's early works, however, were very restrained, characterized by strict adherence to all the techniques and rules of Chinese calligraphy. Nine years have passed, during which he has been living in Israel except for short visits to Japan, and Ishii's artistic style has almost completely changed. He has virtually freed himself of the conventions, and now his brushstrokes are personal, spontaneous.

There are eight focal works in the exhibition, representing the four oriental religions: Shinto, Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism. The symbols, selected by Ishii with great care, have deep meanings related to each of those faiths. Each faith is represented by two words or concepts which characterize it, according to the artist. In the first group, related to Shinto, the word shimpi combines shin (pronounced here as shim for convenience, or as kami - a Shinto deity), with hi - here pronounced as pi for the same reason - meaning "concealed". The word embodies the elusive character of the Shinto gods. The second work is the word kotodama meaning "the soul of the language". These words are thought to have special powers employed or handed down to mankind by the Shinto deities, able to influence the environment, the body and the soul. The two works are perhaps connected through man's need for words to express something that is invisible to him.

The second pair of works is linked to Buddhism. The word bushin is compounded of Butsu - "Buddha", and shin (also called kokoro in Japanese) - meaning "heart". "Buddha" means "enlightenment", or one who has achieved it, i.e. "the enlightened". Thus "the heart of enlightenment" is the state in which man succeeds in achieving a sense of wellbeing without striving for it. The other expression, mujo, means "change" or "transience". The enlightened realize that everything in life is ephemeral, that there is no permanence. Accepting the transience of existence is a condition for wellbeing, for enlightenment, to be forever reprieved from suffering. According to Buddhist belief, the fate of all who pursue transient material acquisitions is eternal suffering.

Two works connected with Taoism come next. The expression taikyoku means "the ultimate basis". Taikyoku - better known to us as tai chi - is an exercise, a series of movements or actions. The same word, written with other characters, means "unification of opposites". It teaches us about the unification of Yin and Yang - "the opposites" - in Taoism. The second work is chuki, meaning "vital energy". According to the Tao, everything contains a vital energy that must be preserved. Maintaining a balance between opposites is one way to preserve this energy, as are Tai Chi exercises and martial arts such as chi kong.

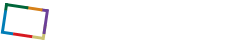

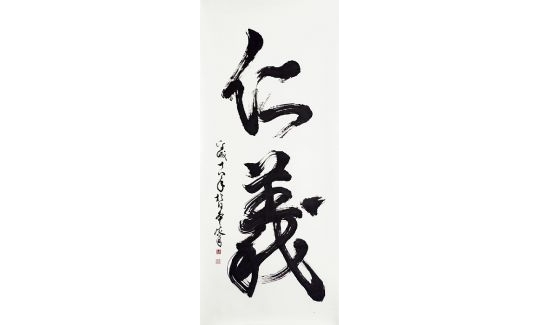

The fourth pair of works focuses on Confucianism. Of the five virtues - generosity, honesty, courtesy, wisdom and sincerity - the basis of the Confucian ethic, Ishii has chosen four. Reichi is composed of the characters for "courtesy" and "wisdom". The other is jingi, meaning "generosity and justice". The Confucian principles instruct us to behave wisely, courteously, generously, justly.

Before commencing work, Ishii performs many exercises, both in calligraphy and in chi kong and tai chi, intended to arouse the vital energies of body and soul. Only when he feels ready does he begin to create. No preparatory sketches are made for ink paintings, and no corrections or modifications can be made to the work. Thus random becomes imperative, and the beauty of the writing lies in its spontaneity, together with the artist's absolute command of brush and ink.

The knowledge that is at the root of ink painting and calligraphy cannot be expressed in words. Inexplicably, the artist's body and hand know their craft. There is a preference for the direct approach as opposed to a considered reliance on technique. Even the intention to create a specific work can lead to failure, and only when the action is spontaneous, mindless (mu-shin), without preconceived notions, can the artist succeed. Accordingly, a "good" painting is not necessarily the one produced after hours of labour and effort have been invested in its production. It is created quickly, concisely. Even though it conveys a sense of simplicity, it is not simple at all. Simplicity is required for dealing with the complexities of life, and can thus be the most complicated of things. A deliberate attempt to achieve simplicity is doomed to failure. It is achieved by means of spontaneous action (Chinese: wu-wei). An artist practices for years in order to achieve this spontaneity, so that together with the simplicity evident to the eye, there is also an ongoing process of method and persistence.

In his calligraphic works in the style of sosho and gyoso (a combination of gyosho and sosho), the strong outlines of the characters are merged and painted with great abstraction, attempting to convey, in a few strokes and patches of ink, an entire cosmos. The artist dips his brush in the ink only once. Hence it is possible to follow the movement of the brush according to the density of the ink, and even to ‘see' the time that elapses from point to point. The density of the ink fades, decreases till it disappears. The empty spaces in a work are just as significant as those covered with the dark ink.

In evaluating a work, great importance is attached to harmonious balance between the different elements - the symbols and the empty spaces around and inside them. Empty spaces are also unexpectedly present in the brushstrokes themselves. They are called hikaku - "Flying White". In the correct proportion, and without crowding, they can transport the viewer's imagination to what lies beyond what is apparent. This does not mean that the viewer will necessarily comprehend the symbolic meaning, but that the work can present an immediate experience or sense of what it tries to convey.

Ishii also tries to minimalize use of colour in his paintings. An empty space has the same weight as a line or patch of ink. Form seems to emerge from this absence, and absence is indivisible from the form, so that they become indistinguishable from each other. Line, patch and white space are equally valid, and the splashes of ink cannot be defined as "something" resting on "nothing". They and the few brushstrokes convey so much information about expression that viewers can compound them in their own imagination.

In Ishii's paintings, the emphasis is not on the final result but on the process, the formation of the brushstrokes, a unique action that cannot be repeated (ichi-go, ichi-e). One could, perhaps, declare that for the artist the work exists for as long as it is happening, with no monumental existence in time. There is a strong feeling that the strength of a painting lies in the moment of its making. It is not a copy of nature, but a natural process whose principle is in the event, the artist's attempt to absorb what is essential and convey it with precision. The exclusive use of black ink implies that, from the outset, the work is not intended as a direct representation of something else - but a process or activity in its own right.