Landscape (sansui-ga) is one of three artistic subjects deriving from the Chinese classification of art. The other two are: birds and flowers (kacho-ga) - to which the Tikotin Museum devoted an exhibition in 2004, and figures (jimbutsu-ga).

By the year 500 C.E. Chinese intellectuals and artists had already laid the foundations of landscape painting that expressed philosophical principles and depictions of the beauties of nature. This included lofty mountains, misty slopes, rivers and waterfalls in which man appears as an occasional and transient presence, dwarfed by the forces of nature. The idealized natural form, modified and monochromatically repeated over the centuries, is explained as a synthesis of Confucian and Buddhist concepts. The Confucian philosophy of nature embodies a preordained value for every single entity in the universe, while Buddhism acknowledges the existence of a transitory world. In art, there is a clear mean for every mountain, tree, or figure. Natural beauty is intellectually integrated, and reflects the depth of the Chinese awareness of nature, assessed in relation to ideal form. This tradition thus makes an important contribution to art, as did the ideal physical proportions in the art of Ancient Greece.

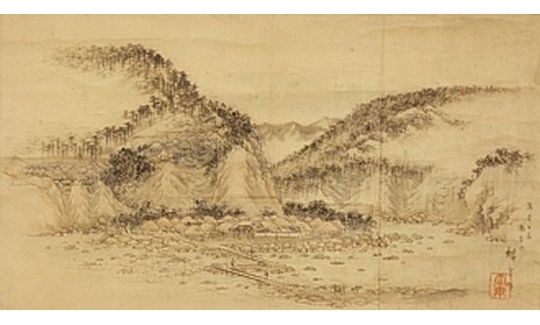

During the Song dynasty (960-1279), these principles were expressed in painting. Styles, compositions, and techniques were developed for representing trees, mountains and rocks in ink-paintings. The style of the Chinese artists Tung Yuan and Chu-jan of the 10th century was the origin of the southern Chinese school of painters. Its influence is evident in the works of renowned Chinese artists from the Yuan era (1279-1368) up to the Wu school of the Ming period (1368-1644), characterized by rounded rock formations produced by extended brushstrokes with the fine point at the tip of the brush.

Conversely, the style of the northern Chinese school is characterized by angular rocks and bold brushstrokes formed with the side of the brush. This style is evident in the works of Hsia Kuei, Ma Yuan, and other court painters of Hangchow during the 13th century, and in those of the artists of the Che school of the Ming dynasty. Their style became the model for Chinese and Japanese artists alike.

In the Heian period (794-1185) in Japan, they were painting trees, mountains and lakes as backgrounds to Buddhist religious themes or the seasons of the year (shiki-e). But the conspicuous philosophical element of sansui-ga only appeared in the Japanese landscape paintings in the 15th century. With the arrival of Zen, a great number of Chinese paintings from the Song and Yuan eras reached Japan. Japanese artists, like Shubun, a monk of the Shokokuji Temple, were inspired by the motifs of the monks and academic artists of the Chinese court, and they too began to depict idealized scenes. The artist Shesshu Toyo (1420-1506), who had visited China, created powerful depictions of the forces of nature by means of the dynamic brushstrokes so characteristic of his work.

The sansui-ga tradition is contrary to that of the European artists of the Renaissance, who set man at the centre of their works, using landscape merely as background. In Chinese and Japanese landscape painting, man is just a random, transient phenomenon of existence. Unlike the Dutch artists who began painting realistic scenes in the 17th century, the sansui-ga artists discarded realism in their attempts to convey a universal poetic atmosphere.

The paintings of the northern Chinese school also inspired the Japanese landscape painters of the Muromachi era (1333-1568) and others artists working in the 16th century, but in the 18th century the influence on Japanese art derived from the Nanga (bunjinga) school, particularly that of the landscape artists of the southern Chinese school.

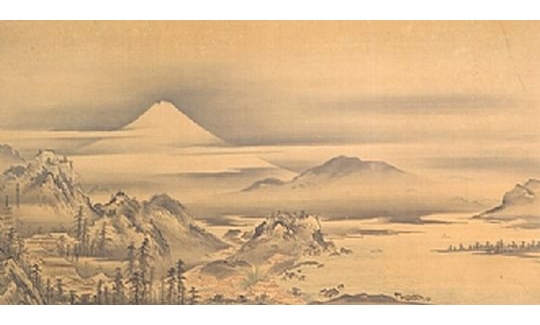

In the 15th century, the Japanese artists began depicting the landscapes of their own country, though they still adhered to the Chinese style and techniques. This is evident in the ink-paintings of many artists of the Kano school, which began at this time and continued throughout the Tokugawa era (1603-1868), when it became the "official" school of painting. Since the Kano artists were neither priests nor monks, they did not create works with religious content. Apart from painted scrolls, they embellished screens and sliding doors for elegant palaces and castles. Obviously, such works had to be organized in clear, balanced compositions since they were intended for decoration. Great precision, rather than emotional content, was required in expressing the chosen subject. Hence these paintings are more evocative than the landscapes of the Chinese Song period.

In the 19th century, artists like Maruyama Okyo (1733-1795) and Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) introduced a new trend in landscape painting, quite different from the conceptual sansui-ga. This more realistic style was known as fukei-ga (realistic pictures).

The landscapes in the exhibition were created by Japanese artists from the 15th to the 20th century. They are typical examples of the artists' approach to the Chinese idealization, a striving for academic harmony of form and spirit. The faithful reproduction of the Chinese landscape tradition of the Song era is evident here in the combination of heavy brushstrokes and a subject that is conducive both to meditation and to emotion. For example, a sheet of water and a lonely cottage standing above it, mountains shrouded in mist in the background and a few rocks are composed to convey intellectual serenity and a romantic setting. This is a peaceful rural scene detached from everyday life, where one can find the purity of nature, and contemplate the power of the natural order. The empty spaces in these works express the sense of isolation found in those of the Song artists. Painting was essentially monochromatic, and dimensions were indicated by the force of the brushstroke and the depth of the ink. The ideal balance between mountains, trees, and figures is evident. But these works also have a dramatic atmosphere, created by the mists that convey a sense of size and distance. Their realism emphasizes the seasons of the year, adding the dimension of time to the works. This type of painting was intended for the elite, the educated, the nobility, who understood its philosophical codes.