The cries of battle, the neighing horses on the battlefield, and the clanging of swords striking against each other have long faded away. But the sword is one of the three most sacred symbols of the Shinto belief, which is why it holds a special place in Japanese culture. The myths of Japan relate that the sun-goddess sent her grandson to JapThe cries of battle, the neighing horses on the battlefield, and the clanging of swords striking against each other have long faded away. But the sword is one of the three most sacred symbols of the Shinto belief, which is why it holds a special place in Japanese culture. The myths of Japan relate that the sun-goddess sent her grandson to Japan after giving him a mirror, a crescent-shaped jewel, and a magic sword which her brother, the storm-god found in the belly of a snake with eight heads. These articles were the symbols of power of the Japanese emperors. Making a sword was and is considered a sacred undertaking. Originally, it was the task of the mountain monks (yamabushi), and was then taken over by families whose profession this became, the secrets of sword-making being handed down from father to son. Before beginning to make the sword, the smiths underwent a religious purification ceremony, washing themselves in water, and donning priestly garments and prayed to the gods for success in their efforts.

Japanese swords were made entirely by hand, with no machinery or advanced technology. For forming the metal there were a few simple implements and much dexterity. Thus the sword has been considered as an objet d'art from the very earliest times. In Japan there were some two hundred schools of sword-making, one hundred and twenty of which were founded between the tenth and twelfth centuries, and another eighty between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries. About a thousand renowned sword artists worked in these schools, and there were some ten or twelve thousand others about whom less is known.

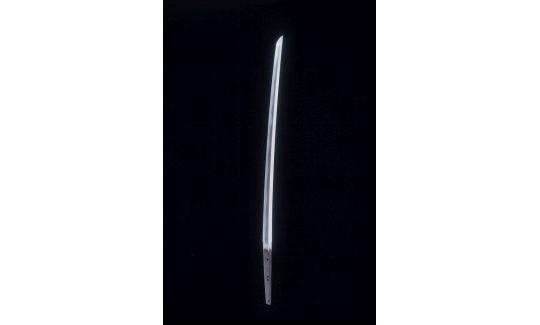

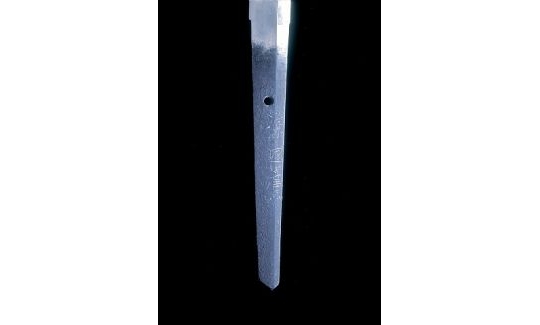

The Japanese sword has more than two hundred components, each of which can be designed in many different ways, resulting in a virtually unlimited number and variety of combinations. The school from which a sword derives can be traced from the way it has been worked. From the beginning of the 10th century, the artist's signature appeared on the tang of the sword, together with the province, the colony and the date on which the blade was tempered.

As of the 7th century BCE, and up to the 3rd century CE, bronze and iron weapons were used in Japan. Forging techniques reached Japan in the 4th century, from China by way of Korea, and the first blacksmiths were apparently Chinese or Korean. Swordsmithing was an extremely specialized profession. From the beginning of the 8th century, Japanese swords were made of very strong steel reinforced by a carbon alloy. Each area of the blade was of different hardness. The sharp side was composed of crystal martensite - an alloy of iron and carbon - and the blunt edge was made of flexible steel. The earliest swords were forged by repeated folding and hammering of the metal, creating about 10,000 layers of steel, which was heated to thousands of degrees in furnaces fired by charcoal. The smith selected the material for the various parts from a thin sheet of metal which had been beaten while incandescently hot. He cooled this sheet by quenching it in water, and then broke it into small, coin-sized fragments. Each fragment was then selected according to colour, granular structure and carbon content before inserting it into the blade. After forging, during which the body of the sword was given its final form by hammering and filing, the blade was tempered and honed. Both of these processes are specific to the Japanese sword. During the tempering, in which the metal is repeatedly heated and cooled, a design known as the "hamon" appears along the sharp side of the blade. This design is one of the sword's most beautiful elements. In olden times the hamon was usually a straight line parallel and close to the edge of the sword. At the beginning of the Kamakura Era (1183-1333) this embellishment began to appear in many lovely patterns. There was a gradual modification from tempering in a straight line (Suguha), to a wavy line (Midare) or curved line (Chojimidare). There were many other patterns - long and short waves, rows of dots reminiscent of fir trees, and others. The school or artist who created the sword can often be identified by these patterns.

Tempering is the final stage of preparation, after which the blade is covered with slip which is an amalgam of polishing powders, molten salts, and other ingredients from the artist's own secret formulae. The body of the sword is coated with a thick layer of this mixture, while the sharp side of the blade is given only a thin coating, and the sword is then fired till this coating becomes a ceramic. The smith heats the blade to the precise temperature required, which he judges by the intensity of the redness as it heats. He then quenches the hot blade by plunging it in water with the sharp side facing downward. Since this side is thinner, as is the coating in this area, it cools faster than the thicker side. As a result, a very strong martensitic steel is formed on this side, which can then be honed to extreme sharpness. The hamon is formed in this way. The sharp side of the sword is almost white, whereas the body of the blade is a darker blue-grey. Between the body of the blade and the hamon is an area in which shining dots of martensite appear. When large enough to be visible to the naked eye they are called Nie, and when they are indistinguishable, appearing to cloud the surface, they are called Nioi. The flexibility, strength and sharpness of the Japanese sword have made it a powerful weapon.

Filing is done by another professional, and not by the swordsmith himself. The polisher uses a series of whetstones of increasing fineness, together with water. This polishing files the outer surface of the sword, revealing the hamon without distorting its construction.

Antique swords (Jokoto) have been found in the ancient burial grounds of the Kofun era (300-710). These old swords are straight, with a short point, and were sharpened on both edges, giving them a rhomboid cross-section. In the Nara period (710-794) and up to the middle of Heian era (794-1185) swords were still straight, similar to those found in the burial ground. They were short and light, and were apparently used for stabbing rather than cutting. As of the 10th century swords became longer and slightly curved, with only one sharp edge.These were suitable for mounted warriors, and could be used for both thrusting and stabbing. The hafts were long, made of wood encased in sharkskin or trigon skin. A wooden bolt (Mekugi) was inserted into the tang of the blade through a matching hole in the haft to join the two parts. On both sides of the haft two metal mounts (Menuki) were joined to the fish skin covering with a cord wound about the haft, which also helped to strengthen the swordsman's grip. At the upper end of the haft there was a cover, and a metal ring at the lower end (Fuchi-kashira), and between haft and blade a metal disc protected the hand. Each metal accessory had its appropriate decoration and ornament. The Japanese sword was enclosed in a wooden scabbard (Saya), which was changed by the warriors as required. Metal-covered scabbards were used in battle, simple wooden sheaths were used when travelling, and decorated, lacquered scabbards were worn with ceremonial dress. (For additional information, see The Tsuba (handguard) and other Metal Accessories)

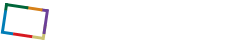

From the middle of the Heian era, and during the Kamakura Period, great advances were made in swordsmithing. The swords created at this time were known as "old swords" (Koto). Warriors usually carried two swords. The long sword (Tachi) was slung on the left side with the blade pointing downward so that the mounted warrior could draw it easily. This sword was elegantly curved, the blade gradually slimming down towards the point. The Tachi varied in length from 45 to 70 centimetres. Beside the long sword hung the short dagger (Tanto), 30 centimetres long, usually employed in hand-to-hand fighting.

Swords made in the Kamakura Era are considered the finest in the world, both artistically and technically, and were even exported to China and Korea. In this period, schools of metalworking began to appear in many Japanese provinces, and famous swords had names, and were considered as valuable assets. In the Muromachi Period (1333-1568), as the production of swords increased, their quality declined due to extended civil wars. Closely-guarded secrets of swordmaking were lost, and sword artists were assessed by the number of swords they produced rather than the quality. Nonetheless, some fine swords were made between 1400 and 1450, particularly in the province of Bizen (today Okayama Prefecture). At this stage the sword was shorter and straighter than the traditional Tachi, and was known as the Katana. It was adapted to fighting on the ground rather than on horseback. In such battles the speed of drawing the sword from its scabbard to attack could be critical for life or death, so that it was carried in the belt of the kimono, pointing upward, which allowed it to be drawn and to strike in one continuous movement. These swords were slightly broader, with a bigger point for piercing the opponent's armour. The blade was 50-60 centimetres long, and less curved than the tachi. The long sword was wielded with both hands because of its size and weight, so that warriors carried no shield, as was customary in the West. With the katana the samurai carried a shorter sword called "Wakizashi", which was also inserted through the girdle, with the blade pointing upward. The Wakizashi blade was between 35 and 50 centimetres long. This sword was sometimes worn indoors because the long sword had been left at the entrance to a house as a sign of trust in the host. Together, the pair of swords were called "Daisho" (long and short), and they were made by the same artist. The dagger (Aiguchi), which had no handguard, was also used, either in self-defence, or for suicide.

In the Azuchi-Momoyama era (1568-1600) and the Edo period (1603-1868) there was a renewal of interest in sword-smithing, in particular by the expert traditional swordsmiths, who tried to reproduce the high quality old swords. The swords they made are known as "Shinto" (new sword). These artists also began to use iron known as "namban" imported to Japan by the Dutch, (namban - "southern barbarians" - an epithet for foreigners). The swords are consequently lighter in colour.

The samurai, who had to be certain that his sword was sharp, used to test it on chunks of iron, old helmets, or thick straw billets. In the Edo period, especially the 18th century, which was a time of peace and prosperity, the samurais were compelled to try out their swords on the bodies of executed criminals (Tameshigiri). On the hafts of such swords can be seen notation of the results of these tests, with the name of the executioner and the date in gold inlay.

Also in the Edo period, the swordsmiths began to decorate swords according to the status of their owners. In Japan, the only country in the world where men were forbidden to wear jewellery, the embellished and decorated sword was considered as an adornment and a medium for artistic expression. Wealthy merchants, especially those from Osaka, carried swords. From the beginning of the 19th century up to the end of Edo, new swords were made (Shinshinto - new new swords) in an attempt to revive this long and noble tradition. In the Meiji period (1868-1912) modernization reached Japan, which then rejected its ancient and traditional culture. In 1870 the Meiji ruler forbade the carrying of swords in public places, and permitted only a very limited number of swordsmiths to continue their craft so as to maintain the tradition. As a result, many swords were destroyed, and the marvellously decorated sections were left in the hands of private collectors and museums. In World War II swords seized by the Americans were crushed by steamrollers and then thrown into the sea. After the war, many swords were brought to Europe and America as souvenirs, as a result of which Japanese owners were ordered to register their swords with the police. This order is still in force.

To the samurai his sword was not merely a weapon. It was a symbol of his courage, his status, and his absolute fidelity to his lord. It was "the soul of the warrior", according to the edict of the military governor Tokugawa Ieyasu said in 1615. Today, samurai swords are still handed down from generation to generation as precious legacies. an after giving him a mirror, a crescent-shaped jewel, and a magic sword which her brother, the storm-god found in the belly of a snake with eight heads. These articles were the symbols of power of the Japanese emperors. Making a sword was and is considered a sacred undertaking. Originally, it was the task of the mountain monks (yamabushi), and was then taken over by families whose profession this became, the secrets of sword-making being handed down from father to son. Before beginning to make the sword, the smiths underwent a religious purification ceremony, washing themselves in water, and donning priestly garments and prayed to the gods for success in their efforts.

Japanese swords were made entirely by hand, with no machinery or advanced technology. For forming the metal there were a few simple implements and much dexterity. Thus the sword has been considered as an objet d'art from the very earliest times. In Japan there were some two hundred schools of sword-making, one hundred and twenty of which were founded between the tenth and twelfth centuries, and another eighty between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries. About a thousand renowned sword artists worked in these schools, and there were some ten or twelve thousand others about whom less is known.

The Japanese sword has more than two hundred components, each of which can be designed in many different ways, resulting in a virtually unlimited number and variety of combinations. The school from which a sword derives can be traced from the way it has been worked. From the beginning of the 10th century, the artist's signature appeared on the tang of the sword, together with the province, the colony and the date on which the blade was tempered.

As of the 7th century BCE, and up to the 3rd century CE, bronze and iron weapons were used in Japan. Forging techniques reached Japan in the 4th century, from China by way of Korea, and the first blacksmiths were apparently Chinese or Korean. Swordsmithing was an extremely specialized profession. From the beginning of the 8th century, Japanese swords were made of very strong steel reinforced by a carbon alloy. Each area of the blade was of different hardness. The sharp side was composed of crystal martensite - an alloy of iron and carbon - and the blunt edge was made of flexible steel. The earliest swords were forged by repeated folding and hammering of the metal, creating about 10,000 layers of steel, which was heated to thousands of degrees in furnaces fired by charcoal. The smith selected the material for the various parts from a thin sheet of metal which had been beaten while incandescently hot. He cooled this sheet by quenching it in water, and then broke it into small, coin-sized fragments. Each fragment was then selected according to colour, granular structure and carbon content before inserting it into the blade. After forging, during which the body of the sword was given its final form by hammering and filing, the blade was tempered and honed. Both of these processes are specific to the Japanese sword. During the tempering, in which the metal is repeatedly heated and cooled, a design known as the "hamon" appears along the sharp side of the blade. This design is one of the sword's most beautiful elements. In olden times the hamon was usually a straight line parallel and close to the edge of the sword. At the beginning of the Kamakura Era (1183-1333) this embellishment began to appear in many lovely patterns. There was a gradual modification from tempering in a straight line (Suguha), to a wavy line (Midare) or curved line (Chojimidare). There were many other patterns - long and short waves, rows of dots reminiscent of fir trees, and others. The school or artist who created the sword can often be identified by these patterns.

Tempering is the final stage of preparation, after which the blade is covered with slip which is an amalgam of polishing powders, molten salts, and other ingredients from the artist's own secret formulae. The body of the sword is coated with a thick layer of this mixture, while the sharp side of the blade is given only a thin coating, and the sword is then fired till this coating becomes a ceramic. The smith heats the blade to the precise temperature required, which he judges by the intensity of the redness as it heats. He then quenches the hot blade by plunging it in water with the sharp side facing downward. Since this side is thinner, as is the coating in this area, it cools faster than the thicker side. As a result, a very strong martensitic steel is formed on this side, which can then be honed to extreme sharpness. The hamon is formed in this way. The sharp side of the sword is almost white, whereas the body of the blade is a darker blue-grey. Between the body of the blade and the hamon is an area in which shining dots of martensite appear. When large enough to be visible to the naked eye they are called Nie, and when they are indistinguishable, appearing to cloud the surface, they are called Nioi. The flexibility, strength and sharpness of the Japanese sword have made it a powerful weapon.

Filing is done by another professional, and not by the swordsmith himself. The polisher uses a series of whetstones of increasing fineness, together with water. This polishing files the outer surface of the sword, revealing the hamon without distorting its construction.

Antique swords (Jokoto) have been found in the ancient burial grounds of the Kofun era (300-710). These old swords are straight, with a short point, and were sharpened on both edges, giving them a rhomboid cross-section. In the Nara period (710-794) and up to the middle of Heian era (794-1185) swords were still straight, similar to those found in the burial ground. They were short and light, and were apparently used for stabbing rather than cutting. As of the 10th century swords became longer and slightly curved, with only one sharp edge.These were suitable for mounted warriors, and could be used for both thrusting and stabbing. The hafts were long, made of wood encased in sharkskin or trigon skin. A wooden bolt (Mekugi) was inserted into the tang of the blade through a matching hole in the haft to join the two parts. On both sides of the haft two metal mounts (Menuki) were joined to the fish skin covering with a cord wound about the haft, which also helped to strengthen the swordsman's grip. At the upper end of the haft there was a cover, and a metal ring at the lower end (Fuchi-kashira), and between haft and blade a metal disc protected the hand. Each metal accessory had its appropriate decoration and ornament. The Japanese sword was enclosed in a wooden scabbard (Saya), which was changed by the warriors as required. Metal-covered scabbards were used in battle, simple wooden sheaths were used when travelling, and decorated, lacquered scabbards were worn with ceremonial dress. (For additional information, see The Tsuba (handguard) and other Metal Accessories)

From the middle of the Heian era, and during the Kamakura Period, great advances were made in swordsmithing. The swords created at this time were known as "old swords" (Koto). Warriors usually carried two swords. The long sword (Tachi) was slung on the left side with the blade pointing downward so that the mounted warrior could draw it easily. This sword was elegantly curved, the blade gradually slimming down towards the point. The Tachi varied in length from 45 to 70 centimetres. Beside the long sword hung the short dagger (Tanto), 30 centimetres long, usually employed in hand-to-hand fighting.

Swords made in the Kamakura Era are considered the finest in the world, both artistically and technically, and were even exported to China and Korea. In this period, schools of metalworking began to appear in many Japanese provinces, and famous swords had names, and were considered as valuable assets. In the Muromachi Period (1333-1568), as the production of swords increased, their quality declined due to extended civil wars. Closely-guarded secrets of swordmaking were lost, and sword artists were assessed by the number of swords they produced rather than the quality. Nonetheless, some fine swords were made between 1400 and 1450, particularly in the province of Bizen (today Okayama Prefecture). At this stage the sword was shorter and straighter than the traditional Tachi, and was known as the Katana. It was adapted to fighting on the ground rather than on horseback. In such battles the speed of drawing the sword from its scabbard to attack could be critical for life or death, so that it was carried in the belt of the kimono, pointing upward, which allowed it to be drawn and to strike in one continuous movement. These swords were slightly broader, with a bigger point for piercing the opponent's armour. The blade was 50-60 centimetres long, and less curved than the tachi. The long sword was wielded with both hands because of its size and weight, so that warriors carried no shield, as was customary in the West. With the katana the samurai carried a shorter sword called "Wakizashi", which was also inserted through the girdle, with the blade pointing upward. The Wakizashi blade was between 35 and 50 centimetres long. This sword was sometimes worn indoors because the long sword had been left at the entrance to a house as a sign of trust in the host. Together, the pair of swords were called "Daisho" (long and short), and they were made by the same artist. The dagger (Aiguchi), which had no handguard, was also used, either in self-defence, or for suicide.

In the Azuchi-Momoyama era (1568-1600) and the Edo period (1603-1868) there was a renewal of interest in sword-smithing, in particular by the expert traditional swordsmiths, who tried to reproduce the high quality old swords. The swords they made are known as "Shinto" (new sword). These artists also began to use iron known as "namban" imported to Japan by the Dutch, (namban - "southern barbarians" - an epithet for foreigners). The swords are consequently lighter in colour.

The samurai, who had to be certain that his sword was sharp, used to test it on chunks of iron, old helmets, or thick straw billets. In the Edo period, especially the 18th century, which was a time of peace and prosperity, the samurais were compelled to try out their swords on the bodies of executed criminals (Tameshigiri). On the hafts of such swords can be seen notation of the results of these tests, with the name of the executioner and the date in gold inlay.

Also in the Edo period, the swordsmiths began to decorate swords according to the status of their owners. In Japan, the only country in the world where men were forbidden to wear jewellery, the embellished and decorated sword was considered as an adornment and a medium for artistic expression. Wealthy merchants, especially those from Osaka, carried swords. From the beginning of the 19th century up to the end of Edo, new swords were made (Shinshinto - new new swords) in an attempt to revive this long and noble tradition. In the Meiji period (1868-1912) modernization reached Japan, which then rejected its ancient and traditional culture. In 1870 the Meiji ruler forbade the carrying of swords in public places, and permitted only a very limited number of swordsmiths to continue their craft so as to maintain the tradition. As a result, many swords were destroyed, and the marvellously decorated sections were left in the hands of private collectors and museums. In World War II swords seized by the Americans were crushed by steamrollers and then thrown into the sea. After the war, many swords were brought to Europe and America as souvenirs, as a result of which Japanese owners were ordered to register their swords with the police. This order is still in force.

To the samurai his sword was not merely a weapon. It was a symbol of his courage, his status, and his absolute fidelity to his lord. It was "the soul of the warrior", according to the edict of the military governor Tokugawa Ieyasu said in 1615. Today, samurai swords are still handed down from generation to generation as precious legacies.