During the Edo period, various laws and prohibitions were imposed on the Japanese public. The Tenpô Reforms of 1841 forbade luxury. In 1842, a special law was enacted dealing with woodblock prints and illustrated books. Among other things, the law forbade the publication of prints depicting Kabuki actors, courtesans, geisha and eroticism, and banned the production of colour prints with more than eight colours. These restrictions made it increasingly difficult for the publishers and print artists. Therefore, Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1798-1861) and his students depicted forbidden subjects in a humorous and satirical guise and in political caricatures. They did so at great risk to themselves. During the Meiji period, caricature prints were published in Japan in large numbers. These prints are to some extent the product of these restrictive laws.

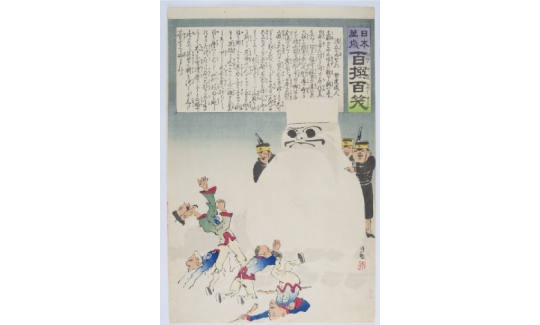

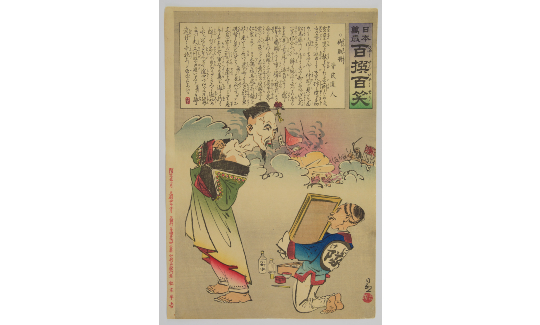

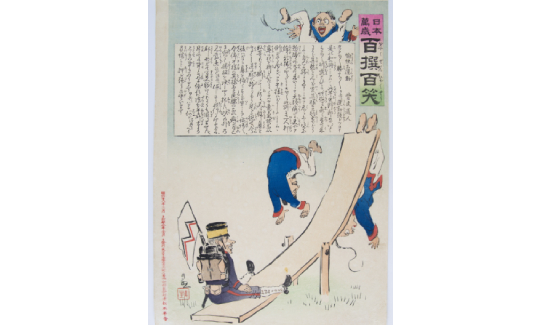

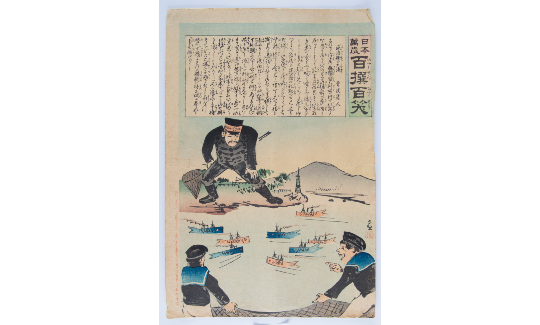

Satirical prints of various artists were published during the Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895) and the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905). Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847-1915), designed comic prints (giga), which depicted the enemy during the war with contempt. His most famous series is "Long Live Japan: One Hundred Selections, One Hundred Laughs" (日本萬歳,百撰百笑; Nihon banzai; Hyakusen hyakushô). The name of the series is a pun created by exchanging Chinese characters with the same pronunciation. The meaning of the original phrase is "Ever Victorious" (百戦百勝; One Hundred Wars, One Hundred Triumphs).

The publisher of the series was Matsuki Heikichi and Nishimori Takeki (1862-1913) compiled the text which appears at the top of each print. Nishimori’s pseudonym, Koppi Dôjin, appears on the right hand-side of the text. The text is rich in remarks, puns and irony.

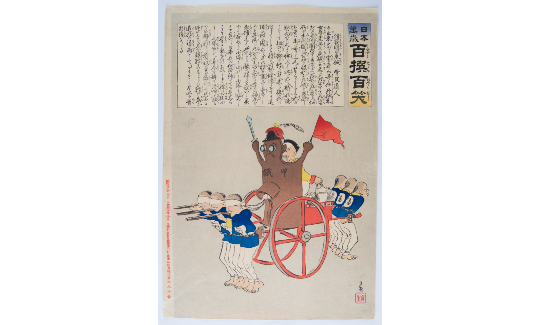

The series consists of three parts, which are a satire about Japan's enemies - the Chinese in the Sino-Japanese War and the Russians in the Russo-Japanese War. It ridicules the enemy, their war effort and leaders, and at times, it may appear racist in nature. The first part of the series "Long Live Japan: One Hundred Selections, One Hundred Laughs", consists of 50 prints, and was published from September 1894 to August 1895. The second part, entitled "Magic Lantern Society: One Hundred Selections, One Hundred Laughs," which numbers 12 prints, was published from November 1895 to December 1896. The third and final part of the series (86 prints), with a similar title to that of the first part, was published from April 1904 to April 1905. The third part’s satire deals with the Russian enemy, whose soldiers are represented as thin, stupid and feminine, while the Japanese soldiers are portrayed as heroes and brave.

Kiyochika's family was wealthy and respected under the shôgun (military ruler) during the Tokugawa regime (1603-1868), however, when the shôgun was deposed during the Meiji Restoration, they lost their status and left Tokyo. In 1874, Kiyochika returned to Tokyo, his hometown, and found that it had entirely changed. The Meiji government opened the borders of Japan, and after years of isolation, engineers, scientists and architects from the West arrived in Japan. Tokyo was filled with buildings made of bricks, trains and railroad tracks, telegraph poles, steamships etc.

Kiyochika became anti-government in his positions, due in part to his family's loss of status. Often prosecuted for his cartoons, Kiyochika was even arrested several times for designing highly controversial caricatures of government officials. Given his continued opposition to the government, it is surprising that he turned his attention to government propaganda in his cartoons of the Sino-Japanese War and the Russo-Japanese War. The patriotic prints he had designed during the wars were far removed from his satirical cartoons. Kiyochika's portrayal of Chinese and Russian soldiers, his interest in modern technological developments and his continuing attachment to Western realism – all reflect his skill both as painter and caricaturist. His works were nationalistic and his caricatures served as effective tools of propaganda. His prints were very popular at the time, but all that changed after the war with Russia, and Kiyochika returned to painting landscapes.

Another satirical series that was designed during the Russo-Japanese War is the "Subjugation of Russia: Amusing Stories of Victory." The designer of the series is Utagawa Kokunimasa (1874-1944), also known as Baidô, or as Utagawa Kunimasa V. The author of the humorous text is Koppi Dôjin. The series mocks the Russian army for its weakness, arrogance and cowardice. The text is interwoven with onomatopoeic puns - for example, Chinese characters with negative meaning, such as death and suffering, are used instead of names of battlefields because of their similar sound.

During the two wars of the Meiji period, colorful and traditional caricature prints were produced in large numbers. War cartoons were among the latest caricatures, whose publication was the result of the Tenpô Reforms.