Mako Idemitsu (b.1940) is a pioneering video artist, one of the most outstanding in this field in Japan today. During the 1960s and 1970s she lived in New York and Los Angeles. When she returned to Japan, she began creating a series of video works dealing with the relationship between mother and child, with the woman's search for identity, the female experience, her hopes and conflicts, and the familial and social role of the woman in Japan.

Idemitsu has been making films and videos for almost forty years. She is a housewife, married and with two children. At the beginning of her artistic career, she was one of the very few women engaged in film-making, and even today only a handful of them are still working. The general consensus at that time was that "the best thing for a woman is to marry, bear children, and rear them".

While living in the United States, Idemitsu became interested with the Women's Liberation Movement, and saw how the women used their 16 mm. movie cameras to film their activities on the streets of America. This experience had a marked effect on her work which, since that time, has dealt with the female experience and the image that society imposes on women. Idemitsu has always been interested in the multiple roles of womankind - daughter, spouse, mother, housewife, artist. She focuses on the possibility of existing as a woman and, at the same time, as a person in a society and culture dominated by men. Her works deal with the dichotomy that many women feel at times, and this dichotomy can be seen as Idemitu's "trademark". Female loyalty is divided between the role society expects women to fill, and the woman herself - between what society expects her to be and her own identity. Idemitsu cites Simone de Beauvoir (1908-1986), the French feminist author's influence on her work - "People are not born as women. They become women". Her oeuvre derives from preconceived opinions and the repression of women, their struggle to exist both as women and as human beings.

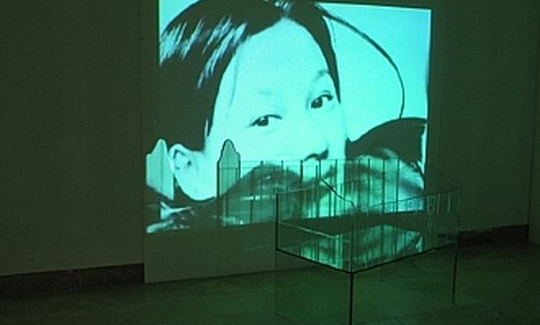

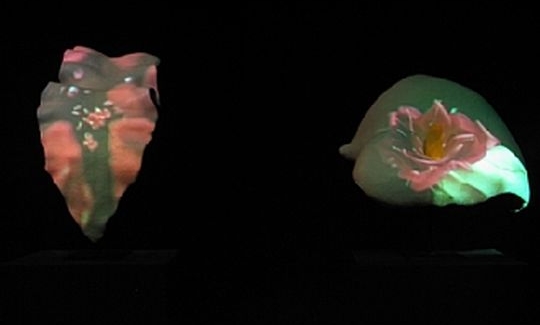

In the installation Still Life (1993-2000), two video films are projected onto two gigantic calla lilies placed side by side in the black space of the hall. On one lily, erect like a phallus, symbol of the male sexual organ, hands pull the petals off a red rose. The petals fall to the ground, spreading like drops of blood on the floor. The hands are then seen trying to pin the petals back on, as if trying to restore the blossom to its original shape. Finally, the flower and the pins are crushed in the hand, crumpled and dead. This rose symbolizes woman.

In the sequence projected on the second lily the pistil, symbolic of the female essence, is missing. We see a woman imprisoned behind an invisible, transparent wall. She begs to be released. There is a woman's voice-over endlessly repeating "Have a good day" and "Welcome home" - phrases that embody the monotony of woman's existence - the invisible cage, the home, promising security, contentment. But is this life happy or intolerable? Is this joy or monotony, misery? In Idemitsu's opinion, all this is due to woman's irrational mode of existence. She believes that a woman's burden has always been to care for the family, no matter how much she resents it. Women cannot fight against this imposition, and are ultimately trampled underfoot, subdued.

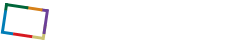

The second installation Real? Motherhood (2000) attacks the myth of maternity. Projected on the wall, and through a child's cradle made of glass, are scenes from the 1960s, of Idemitsu holding one of her children. The photographs from the artist's family album are changed approximately every 10 seconds - the mother lifts the child, the baby suckling, mother and child looking at each other, the baby's innocent smile...... These are interspersed with black-and-white images of the ambiguous expression on the mother's face. Light falling from above onto the glass cradle conveys an impression of sanctity - the cradle is transmuted, for the mother, into an altar. However, Idemitsu insists that this western type of cradle also looks like a coffin, reminding us that "in the midst of life we are in death". So for whom is this celestial cradle intended?

The sacred altar of motherhood is also the deathbed on which mothers lay down their lives as individuals. The display is accompanied by a text from Elisabeth Badintre's "L'amour en plus" (Love Also) - Motherhood is a gift, not a female instinct, as they would have us believe. This penetrating message woven into lovely pictures is characteristic of Mako Idemitsu's style, depicting simultaneously the joys of womanhood and her feelings of constriction, two sides of the same coin.